Anyone familiar with the comics industry knows that the Golden Age was in the 1940s and that every subsequent age has been considered to be a little worse in some way. Sometimes it's the quality of the characters or the stories, sometimes, it's downturns in the economy, and in some cases, it's exploitation from publishers. Various factors, from the CCA to the dark ages of storytelling, have depressed or altered the industry in permanent ways.

Perhaps nothing changed the face of comics quite as much as the exploitation and backlash of the 90s and the near-implosion of the industry. So how did comics as a whole avoid implosion in the 90s?

Did it?

In a way, that's up for debate. It's arguable, in fact, that the comics industry did implode in the 90s. The only thing is, it survived, and it kept growing into the monolith it is today. Time for a history lesson.

Table of Contents

The End of the 80s

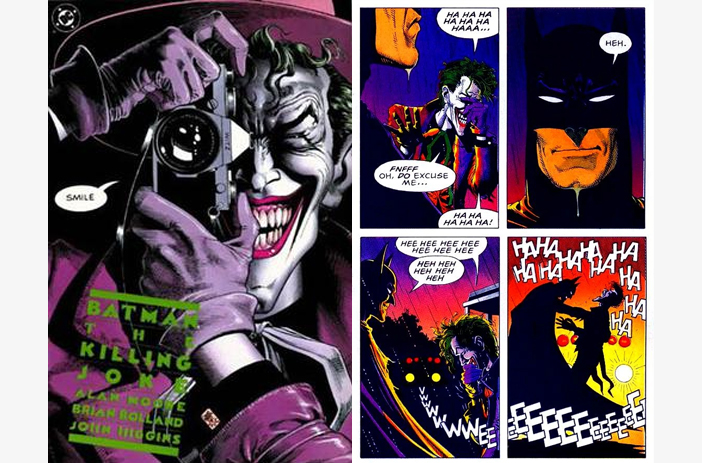

The 1980s is often called the Dark Age of Comics, but that moniker has nothing to do with the industry as a whole. Instead, it's a name that references the tone and subject of the stories being told. Iconic comics like The Killing Joke and Watchmen showcase the more mature, adult themes, darker and grittier tones, and overall kinds of storytelling of the era.

People ate it up. After the bright and shiny morality tales of previous decades, it was a welcome shift, a more "realistic" view of the world and how it might be impacted by highly-powered individuals. Powerful and now-iconic authors and artists were coming into prominence as well, with people like Alan Moore and Frank Miller building their careers.

The 80s was a boom. Perhaps more importantly, this was a near-unprecedented era of great treatment of comic authors and artists. Compensation was fair (unlike today), profits were shared, and everyone thrived in a relatively collaborative environment.

Sure, things weren't perfect. There's always drama under the surface, whether it was institutional racism, sexism both behind the scenes and in the subject matter, or whatever else. Nothing from the 80s was perfect, just like nothing today is perfect.

The Impact of Collectors

One of the biggest shifts to occur in the 80s was the explosion of collectors and collecting as an industry.

Prior to the 80s, people collected comics, but it was more of a genuine passion project for many. People simply liked certain characters, certain artists, certain writers, or whatever else. This happens in any industry; people will collect just about anything if it catches their fancy.

The trouble was, in the 80s, some of the older comics were hitting the market as older collectors needed to exit, either for their own monetary needs or simply to move on from the hobby. Interest in golden-age comics was rising, and so, too, were prices.

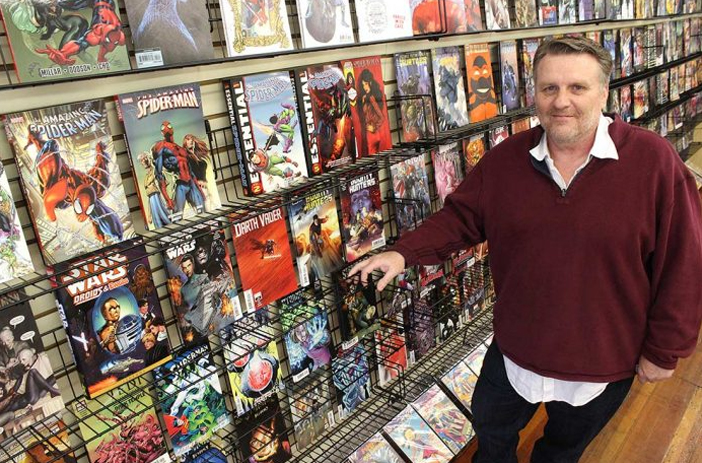

Image source: Google Images

The early 90s showed what comic collectors could potentially pull off. In 1993, the first appearance of Batman in Detective Comics #27 sold for a whopping $55,000. Later, Action Comics #1, the first appearance of Superman, sold for an astonishing $82,500.

Remember, this was early 90s money. To put that in perspective, that Action Comics #1 sold for an equivalent of $167,000 in today's money. Now, that might not seem like much, considering the same comic sold for literal millions a couple of times in the last few years, but it was an incredible amount of money back then.

Can you say Gold Rush?

Collectors flocked to comic stores to buy up older comics, whether entire lines or just key issues, in the hope that rising values could fund a dream home purchase or a retirement a few decades down the line.

What Gives a Comic its Value?

Before we dig into how publishers exploited collectors, it's worth talking about why a comic can be valuable.

What gives a comic its value? In a previous post, we talked about how age affects value; the older a comic is, the more valuable it is, in general. The trick is, age is a big factor, not just because of the age, but because of scarcity. In the 1940s, comics were considered disposable. They were read, enjoyed, returned, discarded, used for papercrafts, or otherwise destroyed. A huge part of the value of 1940s comics comes from how so very, very few of them survived to today.

By the 90s, collectors were buying and saving comics in droves. Scarcity plummeted. And here's the thing about a collector's market: publishers don't get a piece of that pie down the line. DC might have the prestige of having printed Action Comics #1, but if another one sells at auctions for millions, who cares? DC doesn't get a single penny of that sale.

No, publishers know that to tap the collectors market, they need to sell desirable comics up-front.

Image source: Google Images

Value from comics can also come from variations. When you look at lists of the most valuable comics from the 60s, 70s, and 80s, you see that a lot of them were rare variants, like price variations, international editions, and so forth. Misprints and oddities.

This isn't unique to comics, either. There's a huge and thriving secondary market for misprinted trading cards, for example.

Another driver of value is that a comic is a key issue. Key issues mostly come from the introductions of specific characters, and we already saw how in the 60s and 70s, publishers tried the shotgun approach to creating new characters to see who stuck. Key issues also come from key events and happenings in the storylines, like the start of the Secret Wars and other such stories. Keep that in mind.

Publisher Exploitation

Publishers recognized that collectors were going to be a massive market. Of course, they wanted to take advantage of it. They wanted their piece of the pie, and even if they didn't really want to, to let another company make money hand over fist while they languished would be unconscionable. So, they went all-in, industry-wide.

Publishers knew that a significant majority portion of their revenue was now coming from collectors. So, they wanted to find ways to get more money out of those collectors. This is why you saw an absolute explosion in the number of gimmicks launching in the 90s. Such as?

Consider the Variant Cover. A single comic could have, say, two different covers depicting a character or event in different ways. Maybe they had different artists. Maybe they had different primary colors. Maybe they had a metallic and embossed surface. Maybe a set of three covers, when arranged next to each other, would create a triptych panorama.

It never stopped at two or three. Comics would have five, six, or even more variant covers. Now, this hasn't stopped, even today. The record is split between The Amazing Spider-Man, #666, which has an insane 145 different covers, most of which are simple variants with different comic shop logos. The alternative record is The Walking Dead #1, with 253 variants, though most of them are differences from re-issues and re-releases, rather than all of them being released at once. (Neither of these is from the 90s, either! Spiderman is from 2011, and the Walking Dead is from 2003-2023 and onwards.)

This wasn't the only gimmick to exploit collectors, though. The uniqueness and pristine nature of a comic increases its value, so publishers started selling comics in polybags meant to protect and preserve them. Of course, taking a comic out of its bag would decrease its implicit value, so any serious collector who wanted to keep a pristine copy would need to buy two; one to save and one to read. Or more, since they might release with multiple different bag styles, so you had to either gamble on picking the right one or get all of them.

Today, of course, we'd just buy a digital version to read.

Image source: Google Images

Then there were the pack-ins. Posters, postcards, trading cards, holographic cards, music on cassette and CD; anything a publisher could think of to pack in for added value (as long as it was still cheap to produce) would be included.

On top of all of this, content shifted as well. Part of the driver of the success of the 80s was cross-over events and major storylines that brought people together and left permanent marks on the histories of the characters involved.

Well, of course, the 90s turned this up to 11. Perhaps nothing was quite so emblematic of this than the Death of Superman. Killing off Superman would be a massive change in comics, but of course, it didn't stick. But, DC made the Death of Superman into a massive media event, with cross-overs, tie-ins, merchandise, and all manner of other ways to capitalize on the storyline, including, of course, variant covers and huge print runs.

Don't think this was limited to Marvel and DC, either. Not only did all the indie publishers try to get in on this as well, but even more publishers sprang up to try to get their comics going as well. A few of them even stuck around.

Hey, Wait a Minute…

It's around this point that collectors took a look around, blinked a long, slow blink, and realized something. They were being played.

Most of the comics they were buying – the variants, the bags, the events – were artificial. They knew, or realized, that the driving factor of comics value was scarcity and rarity, and these? They were anything but rare. How valuable could a comic from the 90s be decades later when there were still millions of 9-10 grade copies stored away?

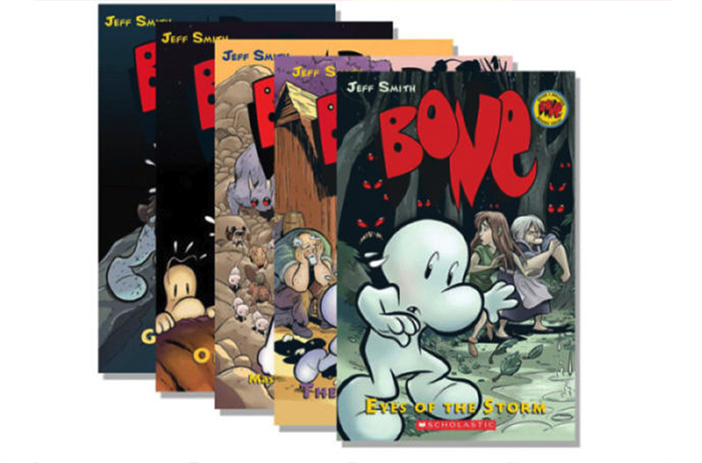

Consider this: the most valuable comics from the 90s are an indie (Bone #1's first printing) at $6,000 and two variants of Venom: Lethal Protector #1 at $1,500. Yeah.

Image source: Google Images

Publishers went all-in on capitalizing on the collector market, and collectors took a collective breath and realized that very same practice meant their comics wouldn't be worth a dang thing. So what happened?

The Crash

As with any bubble, the comic bubble burst. Comic stores, left with huge inventories and dropping interest, no longer made a profit and closed in droves. Publishers that sprang up hoping to sell some new indie gem shuttered when no one gave them the time of day. Variant issues and pack-ins became the subject of jokes, not serious collecting. Major publishers laid off thousands of people, from workers to artists and authors. Marvel reported an annual loss of $48 million dollars in 1994 and filed for bankruptcy in 1996.

Image source: Google Images

So, how did the comics industry avoid the crash? Arguably, it didn't. It just pulled through the other side and worked hard to recover to where it is today.

Lessons Learned

So, did the industry learn a lesson? Well, maybe.

Take a look at a sister industry, like trading cards. Magic the Gathering was created in 1993 and grew by leaps and bounds to become one of the most popular and enduring TCGs ever made. Vintage cards from the 90s sell for incredible amounts of money. Why? Scarcity, desirability, and interest, just like with comics.

So, what is the TCG industry as a whole, or Wizards of the Coast (makers of Magic), doing to avoid the same crash? Well, they're printing a ton of variants, artificially-scarce art variants, limited-run products, serialized cards, and more. Sounds familiar, right?

Image source: Google Images

The lesson learned, at least by many industry executives, is that they can pump a collector's market for all it's worth, jump ship with the money, and move on to another industry to do the same thing.

Comics recovered, and while nothing printed today is likely to ever reach the immense heights of interest, value, and scarcity as something like Action Comics #1, there are thousands of excellent comics, and there's no better time to become a reader and comic fan.

Comics didn't avoid a collapse, but they did recover. Another implosion is unlikely, at least any time soon, or fueled by the same factors. It's a fascinating part of comics history, either way.